Safe Harbor

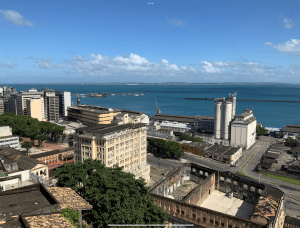

The sounds of containers knocking against one another wake me up. A blue light pierces the sheer curtains. I wait a few minutes before rising from bed. I try not to disturb my wife who likes to sleep another couple of hours. I slip behind the curtain, open the gate and step onto the deck. The waters of the immense Bay of All Saints in front of me have their usual morning tone, pinkish and turquoise depending on the position of the clouds above.

I moved here to Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, two decades ago. A few years ago, I started a documentary about the old port which has seen a lot during the past five centuries. I have been unable to finish it. I have been experiencing a filmmaker’s block—the film form of writer’s block. Could the reason be that I have failed to answer the question that has been haunting me: why did I land on this corner of the earth?

I rarely miss the show of the harbor arousing to a new day. The huge cranes on my right have started their routine of carrying the red, blue and yellow containers from ship to land and land to ship. On my left, the city of Salvador de Bahia, down the hill, is empty. The mosaic of buildings from the colonial to the modern era, those in ruin or obviously decadent, watch the sea in silence. A bus drives through a large avenue. A tugboat passes in front of the old docks, its soft purr reaching my ears as if I were standing a few meters away and not perched on top of the hill. The day will be beautiful, it seems. But the architecture of the clouds also tells me that it might rain.

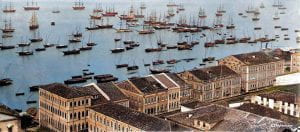

Until the late 19th century and the opening of the Panama Canal, Salvador in Brazil was the biggest port in the South Atlantic. The depth and size of its bay, the second largest in the world after Sydney, made it attractive for the ships coming from Europe looking for a safe haven in the newly discovered land. Amerigo Vespucci, the Italian navigator, is said to have entered it on November 1, 1501, and thus named it The Bay of All Saints after All Saints’ Day. Over the next four centuries, this supposed sainthood proved to be a convenient cover for a somber occupation. Until the abolition of slavery in 1888, the port of Salvador became the second-largest trade center of slaves coming from Africa. Of the 12.5 million slaves estimated to have been imported from Africa to the Americas, 1.5 million arrived in Salvador, about the same number as in Liverpool, only less than in Rio de Janeiro, and three times more than those who landed in the United States. Most were initially dispatched to the sugar plantations of the Northeast of Brazil, later on to the gold and diamond mines of the mountain region of Minas Gerais, and finally to the coffee farms in the south of the country. A good number of them stayed in town to serve in the homes, shops and docks of the Portuguese settlers.

I enjoy walking through the port area, also called Lower City. There I meet the descendants of the slaves. Unlike Higher City, lined with modern buildings and trafficked by few pedestrians, life is vibrant in this part of town. The church bells, the sirens from the departing ships, the music played here and there, the loud voice of the street vendors compose a rich soundtrack. The population is mostly Black, men and women of all ages involved in a large range of manual activities: cooks, waiters, painters, construction workers, bus drivers, parking attendants, salesclerks, tailors. At any time of the day, my path crosses wheelbarrows carrying fruits and vegetables. Many residents own a stand where they copy keys, fix watches, fry some food, xerox a document. Although they have become rarer, grinders of sugar cane sell their concoction for a few cents and the coffee brewer carries different pots on his small decorated wheeled cart. One pot is just black coffee, the next has sugar in it, the third milk and the last both milk and sugar. The coffee man, who calls himself “o cafezinho,” can sell you just one cigarette if you ask. Up until a year ago, once a week, I would get a manicure with a lady in her 70s and a shoeshine with a 90-year-old gentleman, sitting on their broken chairs at a street corner. I didn’t really need it, but I liked their conversation. Although the pandemic has somewhat subsided, they haven’t returned and I wonder if they made it. The only White people you will encounter in Lower City are bankers, lawyers, restaurant and shop owners, civil servants from the various public administrations.

The variety of architecture in Lower City presents to the wanderer the different layers history has left on the city. The office buildings from the post-war period to the late 70’s stand closest to the shore. They are testimony to the last period of prosperity the port has known, when the oil boom and the rich cocoa planters fueled investments in real estate, finance, and art. Further inland, lower buildings with heavily decorated façades, some art deco, others imitations of Neo-classic, used to shelter banks and insurance companies founded during the 19th century by rich locals or adventurous businessmen from England and France. Most have gone out of business leaving the spaces empty. The last layer is made of the first houses and warehouses built at the beginning of port activities. They were erected on the narrow strip of land between the hill and the sea before men pushed the waters away. The houses have several stories: the basement where the slaves lived, the first and second floor where goods were sold and stored, and the next two or three reserved for the owner’s family until they decided to move uptown for more elegant quarters. The large warehouses, called Trapiches, served as customs houses. There, luxury items and textiles from Europe were cleared while sugar, tobacco and cocoa were loaded on the boats anchored to the piers. When not in ruin, almost all the buildings from this period are in precarious condition, often revealing their skeletons of heavy stones stuck together with whale oil.

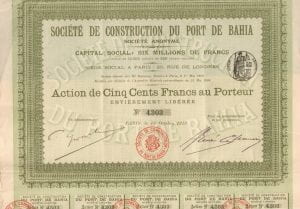

It took me a couple of years to open the envelope of old securities my French grandmother gave me before she passed away. In it, I found bonds from railways in Malaysia, debentures issued by a Moroccan soap factory and, in the middle of another dozen exotic ones, stock certificates of the Construction Society of the Port of Bahia dated 1910. I could not decide if it was a prank played beyond the grave by my grandmother or a sign of destiny. I don’t believe she knew about the town where I moved, and certainly she had no idea that I was living and working in the port area. Like most paper securities from the period before the First World War, these stock certificates are worthless. The French company that issued them to finance the construction of the new port went bankrupt a long time ago. Its owner died penniless in a dingy hotel in Rio de Janeiro.

The Japanese essayist Kenko wrote that “a man’s character, as a rule, may be known from the place where he lives.” If it is true, I wonder what living in a port city reveals about one’s personality. Because I was residing in New York City before I moved to Salvador, I have been questioned many times about the reasons for such a radical change. Was I running away from creditors? Was I looking for a new love after a painful divorce? Some suspected that I was hiding from the police as port cities, in literature and films, have this underground atmosphere about them. A port is the place of choice for brothels attending navy boys in transit. It is also where union leaders make their shady deals with dockers and shipowners. The nicest of the curious concluded that I was your typical wandering Jew. Coming from New York, I was doing the reverse trip of those of my tribe who, in the middle of the 17th century, prohibited to practice their religion by the Portuguese Inquisition, fled Brazil, and boarded some Dutch ships to participate in the foundation of what was then known as New Amsterdam. I wasn’t running or fleeing from anything. To friends and relatives I always gave the same answer: as a teenager, I fell in love with the books of Jorge Amado and wanted to know the city where the famous Brazilian writer staged the drama of Captain of the Sands and Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands. A cute answer but not truthful. I have had a long addiction to the works of Marcel Proust, but I did not move to a beach town in Normandy, nor have any desire to be admitted to the Jockey Club or into the salons of the Paris aristocracy.

In her study “The port, Threshold of the Imagination,” author Aude Mathé claims that the port exercises a strong attraction because it offers “the intimacy of the shelter and the infinity of the horizon, the confinement and the freedom, the link and the rupture.” As such, the harbor is the ideal place for those looking for a refuge and those who want to depart.

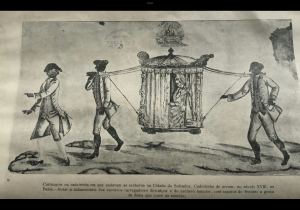

Maybe a port is the ultimate place where one can have big dreams, unconstrained by physical or social limitations. I suspect that to me, and maybe to others, New York lost its appeal as the city of infinite possibilities once it ceased to be a harbor, when cranes and ships were pushed far away from people’s sight, and docks were turned into lofts and shopping centers. In contrast, Salvador has retained its identity as a port city over the centuries. Not coincidentally a significant number of slaves established here, once liberated, sailed back to West Africa, as anthropologist Pierre Verger established in Flux and Reflux – African Diaspora. For most of their uprooted brothers and sisters around the world, it was an impossible dream. But for those enslaved men and women who lived by the Bay of All Saints and each day contemplated boats vanishing in the horizon, it was conceivable. With the permission of the master and the obligation to split the earnings with him, they took extra jobs on the port carrying heavy loads and rich bourgeois in their sedan chairs from Lower City to Higher City. With the money saved, they acquired their freedom for themselves and their relatives and bought their way back to the fatherland.

Yet, there is another dimension to the port, less glorious. This is the place where you watch others leave while you stay, in other words the place of the wannabes. To borrow again the words of Aude Mathé, the harbor offers the possibility of “another life that does not yet exist but, because the port is there, could exist. Everything happens in imagination.” Everything happens and stays in imagination, like a boat permanently stuck on its pier. Like the documentary I started and remains unfinished. I interviewed historians, street vendors, business owners, and shot the port from every possible angle. Twenty hours of footage looking at me on the editing suite, searching for a direction and a meaning.

A few years ago, the municipality of Salvador decided that it was time to revitalize the harbor and the whole Lower City. The town could no longer turn its back to the sea and should exploit better its maritime resources and history, as Barcelona, Baltimore, Marseille and numerous other port cities have done. Universities, public agencies, and enterprises received incentives to set up their operations in the neighborhood. Historic buildings are being rehabilitated and old docks demolished to make room for a new cruise ship terminal and a parking area. Civil servants are being offered rent-subsidized housing. The long-time residents who have stayed while everybody else moved to the modern high-rises uptown are skeptical. It is not that they don’t want to dream of a better future. They just know that they will pay the price for it. The street vendors might not be allowed to operate wherever they want. Real estate speculation will push prices of everything up. The small mom-and-pop stores that have managed to survive will be replaced by global brands. Sadly, the Black population who built the place and survived in it know that their contribution won’t be acknowledged and that many streets will continue to bear the names of slaveowners and traders. An aquarium is being contemplated. A Museum of Brazilian Music recently opened. But there is no talk of a Museum of Slavery like the ones in Liverpool and Cape Town.

Maybe I should finish my documentary focusing on those people who made the port live to this day. Maybe I should tell their story, one of suffering but also of resistance and survival. On arrival from Africa, their ancestors were baptized and received a new name. Many were called Santana or Nascimento to signify their rebirth. They never recovered their original names because the slaveowners demanded that all archives and records be burnt at the time of the abolition. Yet their traditions have endured through the religion they invented by mixing the African gods with the Catholic saints, through the food they cook, and the dances they execute. On the port, the first slave rebellions in Latin America took place. On the port, the slaves and their descendants created a new life for themselves and revived a culture which today is the main point of attraction for the tourists arriving on the gigantic cruise ships.

I do not know if I will solve the mystery of why I came here and why my grandmother left me those stock certificates. I still can’t figure out if I was trying to build a different future for myself or finally anchor my energy somewhere. Maybe I did come here not as a wandering Jew, but as one of those Viking dreamers from Normandy where I was born and raised. Tired of watching the boats going up and down the river Seine, one day they decided to try their luck overseas. I imagine myself as the narrator in the famous novella Le Horla by Maupassant, who lost his mind after an encounter with a mysterious entity, possibly his doppelganger: “Ah! Ah! I remember, I remember the beautiful Brazilian three-master that passed under my windows on its way up the Seine, last May 8! I found it so pretty, so white, so cheerful! The Being was on it, coming from there, where his race was born! And he saw me! He saw my white abode too; and he jumped from the ship on the shore. Oh, my God!” It could be the opening of my film.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário